The hedge is threshold, boundary land. It delineates, marks and divides. Poised between field and field or meadow and lane, it signifies the boundary it simultaneously enacts.

These are ‘landscapes of semiotic uncertainty’ (Kaczmarczyk, p.53). Look carefully at the tangle of bramble and leaf. For the hedgerow is a topological trickster. At times, fecund, green, abundant. At others, bare, barren, denuded. Caught in the twist of seasons, the hedge is home to both green man and ghost. It shifts shape at will.

And ambiguities multiply and enfold. For some, the hedge is a space of nest and burrow. A refuge from predator and storm where it is safe to roost and sleep. Yet this is also a place of danger – for concealment carries both blessing and curse. The eyes that spark in the undergrowth; the rank tang of fox or weasel. In the slanting dusk, the silhouettes of blackthorn and dog-rose invite the unknown. They are ‘uncanny artefacts’ that trouble and disturb (Kaczmarczyk, p.55). Perhaps all hedgerows intimate the zone rouge: this now fertile no-man’s land which bears its stain – and its dark bounty of bone and bullet – through the decades. For every Prince that finds his Sleeping Beauty, lie many others pierced and bleeding on the thorns.

And ambiguities multiply and enfold. For some, the hedge is a space of nest and burrow. A refuge from predator and storm where it is safe to roost and sleep. Yet this is also a place of danger – for concealment carries both blessing and curse. The eyes that spark in the undergrowth; the rank tang of fox or weasel. In the slanting dusk, the silhouettes of blackthorn and dog-rose invite the unknown. They are ‘uncanny artefacts’ that trouble and disturb (Kaczmarczyk, p.55). Perhaps all hedgerows intimate the zone rouge: this now fertile no-man’s land which bears its stain – and its dark bounty of bone and bullet – through the decades. For every Prince that finds his Sleeping Beauty, lie many others pierced and bleeding on the thorns.

Remember too that for the small and wily, the hedge is porous; a permeable barrier though which ancestral paths, the well-marked smeuses, form the old ways through bramble, branch and thistle. Yet, to the large and unseeing, the thorn and briar are as unpassable as the castle wall. But here, as Kaczmarczyk suggests is another ambiguity. For this is not a barrier of stone and mortar but one of fragile stalk and leaf. And there is tension in this contrast (Kaczmarczyk, p.57).

One final duality. By the spinney and at the end of the loke, I find hedges that proclaim their vegetal exuberance. But others, those that border my local lanes, are bushwhacked to a bristly conformity. Yet this will not last. For this is a liminal phase between growth and regrowth. And, in the land of the liminal, the blade only secures temporary control.

Yet there was a time when the blade and digger carried out more potent work. Since 1950 more than half our hedgerows have vanished, condemned ‘as old-fashioned relics that shaded crops, sheltered vermin, wasted space’ (Clifford and King, p.223). And life was lost: the birds flew, the animals retreated. This is, perhaps, a lesson our organisations have failed to learn. Hurdley talks of the ‘increasingly vulnerable position’ of corridors in traditional buildings (Hurdley, p.46). These ‘hedges’ in the office landscape are under threat.

Elsewhere, the devastation has been unleashed. According to Dale and Burrell, seven miles of internal walls in the UK Treasury were removed, ‘literally dismantling the ‘corridors of power’’ (Dale and Burrell, 2010). To justify this destruction, those arguments of productivity and enhanced yield emerge from their 1950’s winding sheet. But here the grain and seed so eagerly sought are those of ‘interactive, complex, open-ended teamwork’ and the diminution of ‘hierarchies or status’ (Hirst and Humphreys, p.1506).

Elsewhere, the devastation has been unleashed. According to Dale and Burrell, seven miles of internal walls in the UK Treasury were removed, ‘literally dismantling the ‘corridors of power’’ (Dale and Burrell, 2010). To justify this destruction, those arguments of productivity and enhanced yield emerge from their 1950’s winding sheet. But here the grain and seed so eagerly sought are those of ‘interactive, complex, open-ended teamwork’ and the diminution of ‘hierarchies or status’ (Hirst and Humphreys, p.1506).

In Hirst and Humphrey’s study of ‘dehedging’ at a UK local authority’s new HQ, there are plaintive echoes of more literal counterparts. As part of the move, ‘de-cluttering’ was encouraged, with sanctions for those ‘who failed to leave their workspace entirely clear of all paperwork and personal items’ (Hirst and Humphreys, p.1516). You can almost hear the bushwhacker’s whine and roar. Yet, three years after this pruning and scraping, ‘many staff had ‘nested’’, their belongings defiantly on display. It is a suggestive metaphor – the domesticity of home and security once more restored to the open, wind-blasted ‘field’.

Elsewhere, the benefits of the prairie office plain are equally elusive. In a new study of food and eating in the workplace, Harriet Shortt observes how, in an open plan office ‘designed with collaboration, togetherness and teamwork in mind’ (Shortt, p.11), one interviewee talked of the loneliness and sense of exclusion such an environment engenders. It is the cake and pastries brought from home and shared ‘on desks and on locker tops’, that bring people back together and reconnect conversations – like birds noisily congregating around the hedgerow’s larder of haws, hips and sloes.

As we have seen, the hedgeless field offers exposure and threat: all who cross or linger are open to the gaze of others. In a recent paper, Hirst and Schwabenland reveal that in a newly configured office, visibility meant that ‘being observed was a constant possibility’ (Hirst and Schwabenland, p.170). For some women this visibility was ‘perceived as uncomfortable or oppressive’ with attendees for job interviews being ‘marked’ for their attractiveness by men in the team (Hirst and Schwabenland, p.170). Similarly, Kingma, in a study of the effects of ‘new ways of working’ in a Dutch insurance company, quoted employees who felt they were ‘constantly being watched’ (Kingma, p.16).

In an echo of this, Shortt notes how several women working flexible arrangements found the hot-desking arrangements exclusionary. They described themselves as ‘nomads’, ‘wandering around the office to find a desk’ – rootless travellers deprived of a home base or shelter from the workplace storm.

So maybe we should campaign for the return of our metaphoric organisational hedges. Allen identified ‘washrooms, copying machines, coffeepots, cafeterias’ as ‘interaction-promoting facilities’ that draw people to them increasing the occurrence of chance encounters and unintended communication (Allen, p.248). And these ‘hedgerow rendezvous’ have value: they are the ‘prime vehicle for transmitting ideas, concepts, and other information necessary for ensuring effective work performance’ (Allen, p.269).

So maybe we should campaign for the return of our metaphoric organisational hedges. Allen identified ‘washrooms, copying machines, coffeepots, cafeterias’ as ‘interaction-promoting facilities’ that draw people to them increasing the occurrence of chance encounters and unintended communication (Allen, p.248). And these ‘hedgerow rendezvous’ have value: they are the ‘prime vehicle for transmitting ideas, concepts, and other information necessary for ensuring effective work performance’ (Allen, p.269).

Hillier stresses the importance of the ‘weak ties’ generated by buildings. These connections to ‘people that one does not know one needs to talk to’ are more likely to break the boundaries of knowledge that solidify when projects, functions and departments are localised (Quoted in Kornberger and Clegg, p.1105). The ‘generative buildings’ that result evoke ‘chaotic, ambiguous, and incomplete space’. It is in these margins – where people who are ‘normally separated exchange ideas and concepts’ – that ‘creative organising and positive power happens’ (Kornberger and Clegg, p.1106). This is fluid, liquid, organic space or, if you prefer, the organisational hedgerows which shelter chance, promise and threat.

For, in these peculiarly liquid times of flux and change, it is important ‘to move quickly and easily across the team boundary’ (Dibble and Gibson, p.926). Contract workers, consultants, fledgling, entrepreneurial ventures all require borders that are permeable and porous. And, like the variety of flora and fauna engendered by the hedgerow, these organisational boundaries can be similarly diverse. Their form may be social, cultural, physical while the flow can involve people, information, resources and status (Dibble and Gibson, p.929).

So, if you hear the bushwhacker’s roar, remember the power of elder, dogwood, hazel and sweet briar. For it in these interlacing boundaries, fertile, pliable and everlastingly liminal, that the inventive and cunning will find the shaded gaps that lead to invention and, maybe, salvation.

Now the hedgerow is blanched for an hour with transitory blossom/Of Snow, a bloom more sudden/Than that of summer

Allen, Thomas J. (1977), Managing the flow of information. MIT Press.

Clifford, S. and King, A. (2006), England in particular: a celebration of the commonplace, the local, the vernacular and the distinctive. Hodder & Stoughton.

Dale, K. and Burrell, G. (2010) ‘All together, altogether better’: the ideal of ‘community’ in the spatial reorganization of the workplace’, in van Marrewijk, A. and Yanow, D. (eds.) Organizational spaces: dematerialising the workaday world. Edward Elgar.

Dibble, R. and Gibson, C. B. (2018) ‘Crossing team boundaries: a theoretical model of team boundary permeability and a discussion of why it matters’, Human Relations, 71(7), pp. 925–950.

Eliot, T.S. (1944) ‘Little Gidding’, in Four Quartets. Faber.

Hirst, A. and Humphreys, M. (2013) ‘Putting power in its place: the centrality of edgelands’, Organization Studies, 34(10), pp. 1505–1527.

Hirst, A. and Schwabenland, C. (2018) ‘Doing gender in the “new office”’, Gender, Work and Organization, 25(2), pp. 159–176.

Hurdley, R. (2010) ‘The power of corridors: connecting doors, mobilising materials, plotting openness’, The Sociological Review, 58(1), pp. 45–64.

Kaczmarczyk, K. and Salvoni, M. (2016) ‘Hedge mazes and landscape gardens as cultural boundary objects’, Sign Systems Studies, 44(12), pp. 53–68.

Kingma, S. (2018) ‘New ways of working (NWW): work space and cultural change in virtualizing organizations’, Culture and Organization, (Online), pp. 1-24.

Kornberger, M. and Clegg, S. R. (2004) ‘Bringing space back in: organizing the generative building’, Organization Studies, 25(7), pp. 1095–1114.

Macfarlane, R. (2015), Landmarks. Hamish Hamilton

Shortt, H. (2018) ‘Cake and the open plan office: a foodscape of work through a Lefebvrian lens’, in: Kingma, S., Dale, K. and Wasserman, V., eds. (2018) Organizational space and beyond: The significance of Henri Lefebvre for organizational studies. Routledge [In Press].

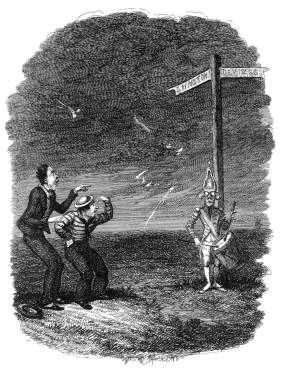

But then, this should not surprise us. For the crossroads is a place of contradictions. A liminal space caught between borders and possibilities. It is a ‘real place between imaginary places – points of departure and arrival’ (Komunyakaa, p.5). We stand poised between where we have been and where we might, in the future, find ourselves. This is the ‘intersection of the timeless moment’ (Eliot, p.42). Opportunity, danger, enchantment, despair, salvation and damnation insinuate themselves, like a twilight mist, around our lonely fingerpost.

But then, this should not surprise us. For the crossroads is a place of contradictions. A liminal space caught between borders and possibilities. It is a ‘real place between imaginary places – points of departure and arrival’ (Komunyakaa, p.5). We stand poised between where we have been and where we might, in the future, find ourselves. This is the ‘intersection of the timeless moment’ (Eliot, p.42). Opportunity, danger, enchantment, despair, salvation and damnation insinuate themselves, like a twilight mist, around our lonely fingerpost. The ambiguity of the crossroads is also seen in the tradition of burying of suicides. Halliday notes that although the law in England stipulated that a suicide should be buried in the King’s highway, the chosen site was often a crossroad by a parish boundary (Halliday, p.82). I frequently pass one such site. In 1785, Richard Knobbs, a brickmaker in the Norfolk village of Hempnall, was suspected of murdering his son and hanged himself from a tree. The junction where he is buried is still known as Nobb’s Corner. Halliday argues that such interment acted as a deterrent. Excluded from the community of a churchyard, burial in a ‘remote, anonymous grave without a funeral was a casting-out; the person no longer belonged to society’ (Halliday p.82). Yet, maybe, such a place provided comfort too: the topographical cross bestowing some remnant of sanctity on the lost and, in every way, marginalised.

The ambiguity of the crossroads is also seen in the tradition of burying of suicides. Halliday notes that although the law in England stipulated that a suicide should be buried in the King’s highway, the chosen site was often a crossroad by a parish boundary (Halliday, p.82). I frequently pass one such site. In 1785, Richard Knobbs, a brickmaker in the Norfolk village of Hempnall, was suspected of murdering his son and hanged himself from a tree. The junction where he is buried is still known as Nobb’s Corner. Halliday argues that such interment acted as a deterrent. Excluded from the community of a churchyard, burial in a ‘remote, anonymous grave without a funeral was a casting-out; the person no longer belonged to society’ (Halliday p.82). Yet, maybe, such a place provided comfort too: the topographical cross bestowing some remnant of sanctity on the lost and, in every way, marginalised. And, as we have intimated

And, as we have intimated  Such ghosts possess other objects too. A long time ago, I asked a colleague to identify an artefact that encapsulated our then organisation. After a pause, he spoke fondly of the chair that his former boss had left behind on retirement. Each time he saw it, he took strength from the memory of his mentor, guide and protector. It had what Weber called the ‘charisma’ of the object’ and Walter Benjamin, ‘the aura of the original’ (Bell, p.817). That chair was not just any chair; it contained a ‘kind of life’.

Such ghosts possess other objects too. A long time ago, I asked a colleague to identify an artefact that encapsulated our then organisation. After a pause, he spoke fondly of the chair that his former boss had left behind on retirement. Each time he saw it, he took strength from the memory of his mentor, guide and protector. It had what Weber called the ‘charisma’ of the object’ and Walter Benjamin, ‘the aura of the original’ (Bell, p.817). That chair was not just any chair; it contained a ‘kind of life’. We also progress in time, a movement governed by – or more accurately suggested by – timetables and schedules. Before 1840, such definitions of time were also inherently fluid. A journey was not just through time but between time with different towns deploying local systems of time. For the Victorians however, the modern railway carriage was, as John Bailey intriguingly explores, liminal in many other ways. If we peek through the smoke-smudged windows, we might discern a place of adventure, blurred identities, erotic escapade and transgression.

We also progress in time, a movement governed by – or more accurately suggested by – timetables and schedules. Before 1840, such definitions of time were also inherently fluid. A journey was not just through time but between time with different towns deploying local systems of time. For the Victorians however, the modern railway carriage was, as John Bailey intriguingly explores, liminal in many other ways. If we peek through the smoke-smudged windows, we might discern a place of adventure, blurred identities, erotic escapade and transgression. Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend or Kafka’s The Castle offer distorted premonitions of the modern labyrinthine organisation. Both Arthur Clennam and K become enmeshed in unknowable bureaucracies where clarity is vigorously suppressed. As the shocked Junior Barnacle – interrupted in his eating of mashed potatoes and gravy – remonstrates: ‘…you mustn’t come into the place saying you want to know, you know’. Knowledge is the ultimate taboo.

Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend or Kafka’s The Castle offer distorted premonitions of the modern labyrinthine organisation. Both Arthur Clennam and K become enmeshed in unknowable bureaucracies where clarity is vigorously suppressed. As the shocked Junior Barnacle – interrupted in his eating of mashed potatoes and gravy – remonstrates: ‘…you mustn’t come into the place saying you want to know, you know’. Knowledge is the ultimate taboo.