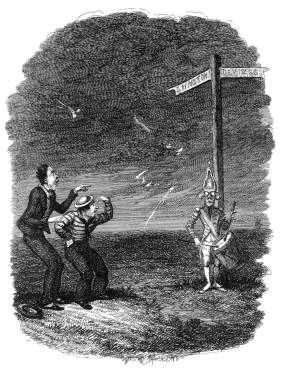

Imagine a country crossroads. It is dusk on a late Autumn afternoon. You are alone – or so you think. There is a grassy triangle where the road divides. A leaning sign – not unlike, in this fading light, a gallows – offers direction. Maybe you are lost and the sense of adventure you earlier felt is now compromised by creeping concern. There is relief that these ways are trodden; but confusion as to which path to take.

But then, this should not surprise us. For the crossroads is a place of contradictions. A liminal space caught between borders and possibilities. It is a ‘real place between imaginary places – points of departure and arrival’ (Komunyakaa, p.5). We stand poised between where we have been and where we might, in the future, find ourselves. This is the ‘intersection of the timeless moment’ (Eliot, p.42). Opportunity, danger, enchantment, despair, salvation and damnation insinuate themselves, like a twilight mist, around our lonely fingerpost.

But then, this should not surprise us. For the crossroads is a place of contradictions. A liminal space caught between borders and possibilities. It is a ‘real place between imaginary places – points of departure and arrival’ (Komunyakaa, p.5). We stand poised between where we have been and where we might, in the future, find ourselves. This is the ‘intersection of the timeless moment’ (Eliot, p.42). Opportunity, danger, enchantment, despair, salvation and damnation insinuate themselves, like a twilight mist, around our lonely fingerpost.

Some folklorists claim the crossroads is ‘the most magical spot in popular tradition’ (Davidson, p.9). In Suffolk, a cure for ague relied on the sufferer going at midnight to a crossroads, turning around three times and then driving a tenpenny nail up to its head in the ground (Ewart Evan, p.86). The potency of iron entwined with the potency of place. Such enchantment may also blur temporal boundaries. Puhvel describes the custom of scattering hemp-seeds at a cross-roads then whispering an incantation. The prize? A glimpse of your future lover (Puhvel, p.170).

Urban settings are not immune from this magic. Ghassem-Fachandi explores how, in the Indian city of Ahmedabad, the magical remains from exorcisms are placed at busy crossroads. Such ‘interstitial spaces, city fords and thresholds, it is said, confuse the evil spirits and ghosts, and they cannot find their way back to their bearer’ (Ghassem-Fachandi, p.24).

Other traditions reinforce such crossings between the living and the dead. In Richardson’s study of thresholds and boundaries in British funeral customs, she notes how, in Wales, the burial procession paused at each crossroads for prayers to be offered (Richardson, p.97). Was this because the cruciform shape suggested a safe and hallowed place; or to confuse the restless spirit and deter it from returning home? Or, maybe, the crossroads acted as stepping stones for the spirit – a physical enactment of the perilous post-mortem journey described in the ancient Lyke Wake Dirge.

From Brig o’ Dread when thou may’st pass,

Every nighte and alle,

To Purgatory fire thou com’st at last;

And Christe receive thy saule.

The ambiguity of the crossroads is also seen in the tradition of burying of suicides. Halliday notes that although the law in England stipulated that a suicide should be buried in the King’s highway, the chosen site was often a crossroad by a parish boundary (Halliday, p.82). I frequently pass one such site. In 1785, Richard Knobbs, a brickmaker in the Norfolk village of Hempnall, was suspected of murdering his son and hanged himself from a tree. The junction where he is buried is still known as Nobb’s Corner. Halliday argues that such interment acted as a deterrent. Excluded from the community of a churchyard, burial in a ‘remote, anonymous grave without a funeral was a casting-out; the person no longer belonged to society’ (Halliday p.82). Yet, maybe, such a place provided comfort too: the topographical cross bestowing some remnant of sanctity on the lost and, in every way, marginalised.

The ambiguity of the crossroads is also seen in the tradition of burying of suicides. Halliday notes that although the law in England stipulated that a suicide should be buried in the King’s highway, the chosen site was often a crossroad by a parish boundary (Halliday, p.82). I frequently pass one such site. In 1785, Richard Knobbs, a brickmaker in the Norfolk village of Hempnall, was suspected of murdering his son and hanged himself from a tree. The junction where he is buried is still known as Nobb’s Corner. Halliday argues that such interment acted as a deterrent. Excluded from the community of a churchyard, burial in a ‘remote, anonymous grave without a funeral was a casting-out; the person no longer belonged to society’ (Halliday p.82). Yet, maybe, such a place provided comfort too: the topographical cross bestowing some remnant of sanctity on the lost and, in every way, marginalised.

So here, at the crossroads, the borders are not just physical but metaphysical. This is where we transgress boundaries to contract with higher powers. Think of a young bluesman meeting the devil at a Mississippi crossroads to seal his own Faustian pact. Yet listen carefully to Robert Johnson’s Cross Roads Blues and there are intimations of more tangible threats. Here, at the rural intersection, cars slow down offering the hitchhiker the promise of a welcome lift – ‘standing at the crossroads, tried to flag a ride’. This is a place of opportunity bearing the gift of progress or return. But with the sun going down, the singer’s plea for salvation – ‘Asked the Lord above “have mercy, now save poor Bob, if you please”‘ – suggests this is also a place of danger. The fear is not, necessarily, that of eternal damnation but one that faced any young black man of that time, alone and far from home: vagrancy charges or, even, lynching (‘Cross Road Blues’, 2018). The crossroads is not a safe place to linger.

So what, you may think, has the liminality of crossroads to do with the organisations in which we work. For surely these are places devoid of such magic, enchantment and old traditions? Yet, look carefully enough, and you will find ghosts, tricksters and graveyards. And, of course, our buildings have physical crossroads (of sorts). Let me describe one to you.

On the fourth floor of a corporate HQ, there is a long, open corridor that leads past a café and then forms a ‘crossroads’ with passages that continue to the restaurant and meeting spaces. At the junction, there is a widening of the corridor – often used for displays – but, always occupied by small groups, talking, chatting, laughing. These constellations – formed by serendipitous encounters – reshape and reform with random regularity. So, where we expect transit, we counter-intuitivly encounter stasis. In Dale and Burrell’s study of space and community, they distinguish two types of spatial formation. Socio-petal arrangements ‘produce spaces where people are encouraged to gather together’ (Dale and Burrell, p.26). In contrast, socio-fugal spaces encourage people to move on and through. But our crossroads here is betwixt and between both socio-petal and socio-fungal. It brings people into constant contact yet then provokes them to linger and commune.

Like the Mississippi cross-roads, this may invoke threat and anxiety. Just who might you bump into? (For the devil can be found anywhere!). Yet there is also the promise of opportunity and fulfilment. Allen notes how organisational traffic patterns directly influence communication by promoting chance encounters and aiding ‘the accomplishment of intended contacts’ (Allen, p.248). This underpins the flow of information and the exchange of problems and experiences. Similarly, Iedema explores how a spatial bulge in a hospital corridor ‘drew people into it’ (Iedema et al, p.43) and, by providing a space where professional boundaries and organisational rules could be suspended, enabled clinical staff to ‘connect formal knowledge to the complexity of in situ work’ (p.52).

So perhaps there is little to distinguish our smart, open plan office intersection from our rural grassy triangle. Just as the latter are ecologically acclaimed as places where ‘a small nature reserve flourishes’ (Clifford and King, p.205), so the former are equally fertile: seeding communication and harvesting knowledge, insight and experience. And like any fragile and threatened ecology, these are valuable spaces we need to recognise and protect.

Allen, Thomas J. (1977), Managing the flow of information. MIT Press.

Clifford, S. and King, A. (2006), England in particular: a celebration of the commonplace, the local, the vernacular and the distinctive. Hodder & Stoughton.

‘Cross Road Blues’ (2018) Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cross_Road_Blues (Accessed: 30 March, 2018).

Dale, K. and Burrell, G. (2010) ‘All together, altogether better’: the ideal of ‘community’ in the spatial reorganization of the workplace’, in van Marrewijk, A. and Yanow, D. (eds.) Organizational spaces: dematerialising the workaday world. Edward Elgar.

Davidson, H.E. (1993) ‘Introduction’, in Davidson, H.E. (ed.) Boundaries & thresholds. The Thimble Press.

Eliot, T.S. (1944) ‘Little Gidding’, in Four Quartets. Faber.

Evans, G.E. (1966), The pattern under the plough: aspects of the folk-lore of East Anglia. Faber.

Ghassem-Fachandi, P. (2012) ‘The city threshold: mushroom temples and magic remains in Ahmedabad’, Ethnography, 13(1), pp. 12–27.

Halliday, R. (2010) ‘The roadside burial of suicides: an East Anglian study’, Folklore, 121 (April), pp. 81–93.

Iedema, R, Long, D. and Carroll, K. (2010) ‘Corridor communication, spatial design and patient safety: enacting and managing complexities’, in van Marrewijk, A. and Yanow, D. (eds.) Organizational spaces: dematerialising the workaday world. Edward Elgar.

Komunyakaa, Y. (1997) ‘Crossroads’, Ploughshares, 23(1), pp. 5-6.

Puhvel, M. (1976) ‘The mystery of the cross-roads’, Folklore, 87(2), pp. 167–177.

Richardson, R. (1993) ‘Death’s door: thresholds and boundaries in British funeral customs’, in Davidson, H.E. (ed.) Boundaries & thresholds. The Thimble Press.

Illustrations

Rodwell, I. (2018) Nobb’s Corner, Hempnall, Norfolk

Rodwell, I. (2018) Fingerpost, Norfolk

We have seen how the corridor is a place that welcomes

We have seen how the corridor is a place that welcomes  Of course, we could read this artwork in another way. By encouraging us to navigate the corridor in a physically prescribed way, we are reminded how space acts as the ‘materialization of power relations’ (Taylor and Spicer, p.330). In Hurdley’s broadcast, the curator of Tyntesfield House describes how the corridor to the ‘virgins’ wing’ (where the female servants lived) was ‘protected’ by the Foucaldian panopticon of the cook’s bedroom: the senitel who detects and deters transgressive behaviour. In other grand houses, corridors are used to demonstrate monetary wealth and cultural learning. At Chatsworth, the Chapel Corridor evokes a grand collector’s gallery bringing together sumptious art works from the Devonshire Collection.

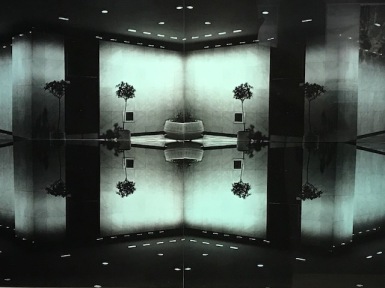

Of course, we could read this artwork in another way. By encouraging us to navigate the corridor in a physically prescribed way, we are reminded how space acts as the ‘materialization of power relations’ (Taylor and Spicer, p.330). In Hurdley’s broadcast, the curator of Tyntesfield House describes how the corridor to the ‘virgins’ wing’ (where the female servants lived) was ‘protected’ by the Foucaldian panopticon of the cook’s bedroom: the senitel who detects and deters transgressive behaviour. In other grand houses, corridors are used to demonstrate monetary wealth and cultural learning. At Chatsworth, the Chapel Corridor evokes a grand collector’s gallery bringing together sumptious art works from the Devonshire Collection. The scent of the uncanny also infuses our quotidian places of work. Should we ever visit after hours or at the week-end, they always invoke, I feel, a sense of the strange. And this is most apparent in the corridors: quiet, denuded, almost sentient in their calm. This effect heightens perception: sounds are subtly amplified; and the signage and art work somehow appear more prominent. We might attribute this to the failure of presence – ‘there is nothing present where there should be something’ (Fisher, p.61). This quality of the eerie is forensically explored by the artist Tim Head in a series of photographic collages showing de-humanised spaces: empty corporate receptions, hotel entrances, underground car parks. Enhanced by pale tinting, the collages portray the uncanny and alien while evoking the melancholy of lost and half-imagined futures.

The scent of the uncanny also infuses our quotidian places of work. Should we ever visit after hours or at the week-end, they always invoke, I feel, a sense of the strange. And this is most apparent in the corridors: quiet, denuded, almost sentient in their calm. This effect heightens perception: sounds are subtly amplified; and the signage and art work somehow appear more prominent. We might attribute this to the failure of presence – ‘there is nothing present where there should be something’ (Fisher, p.61). This quality of the eerie is forensically explored by the artist Tim Head in a series of photographic collages showing de-humanised spaces: empty corporate receptions, hotel entrances, underground car parks. Enhanced by pale tinting, the collages portray the uncanny and alien while evoking the melancholy of lost and half-imagined futures. Our signalling is successful. A black London cab executes a perfect U-turn – a masterclass in precision and confidence – that attracts notice and does little to sate our desire for anonymity. We state our destination, open the door and step inside.

Our signalling is successful. A black London cab executes a perfect U-turn – a masterclass in precision and confidence – that attracts notice and does little to sate our desire for anonymity. We state our destination, open the door and step inside. And, as we have intimated

And, as we have intimated  Such ghosts possess other objects too. A long time ago, I asked a colleague to identify an artefact that encapsulated our then organisation. After a pause, he spoke fondly of the chair that his former boss had left behind on retirement. Each time he saw it, he took strength from the memory of his mentor, guide and protector. It had what Weber called the ‘charisma’ of the object’ and Walter Benjamin, ‘the aura of the original’ (Bell, p.817). That chair was not just any chair; it contained a ‘kind of life’.

Such ghosts possess other objects too. A long time ago, I asked a colleague to identify an artefact that encapsulated our then organisation. After a pause, he spoke fondly of the chair that his former boss had left behind on retirement. Each time he saw it, he took strength from the memory of his mentor, guide and protector. It had what Weber called the ‘charisma’ of the object’ and Walter Benjamin, ‘the aura of the original’ (Bell, p.817). That chair was not just any chair; it contained a ‘kind of life’. We also progress in time, a movement governed by – or more accurately suggested by – timetables and schedules. Before 1840, such definitions of time were also inherently fluid. A journey was not just through time but between time with different towns deploying local systems of time. For the Victorians however, the modern railway carriage was, as John Bailey intriguingly explores, liminal in many other ways. If we peek through the smoke-smudged windows, we might discern a place of adventure, blurred identities, erotic escapade and transgression.

We also progress in time, a movement governed by – or more accurately suggested by – timetables and schedules. Before 1840, such definitions of time were also inherently fluid. A journey was not just through time but between time with different towns deploying local systems of time. For the Victorians however, the modern railway carriage was, as John Bailey intriguingly explores, liminal in many other ways. If we peek through the smoke-smudged windows, we might discern a place of adventure, blurred identities, erotic escapade and transgression.