The hedge is threshold, boundary land. It delineates, marks and divides. Poised between field and field or meadow and lane, it signifies the boundary it simultaneously enacts.

These are ‘landscapes of semiotic uncertainty’ (Kaczmarczyk, p.53). Look carefully at the tangle of bramble and leaf. For the hedgerow is a topological trickster. At times, fecund, green, abundant. At others, bare, barren, denuded. Caught in the twist of seasons, the hedge is home to both green man and ghost. It shifts shape at will.

And ambiguities multiply and enfold. For some, the hedge is a space of nest and burrow. A refuge from predator and storm where it is safe to roost and sleep. Yet this is also a place of danger – for concealment carries both blessing and curse. The eyes that spark in the undergrowth; the rank tang of fox or weasel. In the slanting dusk, the silhouettes of blackthorn and dog-rose invite the unknown. They are ‘uncanny artefacts’ that trouble and disturb (Kaczmarczyk, p.55). Perhaps all hedgerows intimate the zone rouge: this now fertile no-man’s land which bears its stain – and its dark bounty of bone and bullet – through the decades. For every Prince that finds his Sleeping Beauty, lie many others pierced and bleeding on the thorns.

And ambiguities multiply and enfold. For some, the hedge is a space of nest and burrow. A refuge from predator and storm where it is safe to roost and sleep. Yet this is also a place of danger – for concealment carries both blessing and curse. The eyes that spark in the undergrowth; the rank tang of fox or weasel. In the slanting dusk, the silhouettes of blackthorn and dog-rose invite the unknown. They are ‘uncanny artefacts’ that trouble and disturb (Kaczmarczyk, p.55). Perhaps all hedgerows intimate the zone rouge: this now fertile no-man’s land which bears its stain – and its dark bounty of bone and bullet – through the decades. For every Prince that finds his Sleeping Beauty, lie many others pierced and bleeding on the thorns.

Remember too that for the small and wily, the hedge is porous; a permeable barrier though which ancestral paths, the well-marked smeuses, form the old ways through bramble, branch and thistle. Yet, to the large and unseeing, the thorn and briar are as unpassable as the castle wall. But here, as Kaczmarczyk suggests is another ambiguity. For this is not a barrier of stone and mortar but one of fragile stalk and leaf. And there is tension in this contrast (Kaczmarczyk, p.57).

One final duality. By the spinney and at the end of the loke, I find hedges that proclaim their vegetal exuberance. But others, those that border my local lanes, are bushwhacked to a bristly conformity. Yet this will not last. For this is a liminal phase between growth and regrowth. And, in the land of the liminal, the blade only secures temporary control.

Yet there was a time when the blade and digger carried out more potent work. Since 1950 more than half our hedgerows have vanished, condemned ‘as old-fashioned relics that shaded crops, sheltered vermin, wasted space’ (Clifford and King, p.223). And life was lost: the birds flew, the animals retreated. This is, perhaps, a lesson our organisations have failed to learn. Hurdley talks of the ‘increasingly vulnerable position’ of corridors in traditional buildings (Hurdley, p.46). These ‘hedges’ in the office landscape are under threat.

Elsewhere, the devastation has been unleashed. According to Dale and Burrell, seven miles of internal walls in the UK Treasury were removed, ‘literally dismantling the ‘corridors of power’’ (Dale and Burrell, 2010). To justify this destruction, those arguments of productivity and enhanced yield emerge from their 1950’s winding sheet. But here the grain and seed so eagerly sought are those of ‘interactive, complex, open-ended teamwork’ and the diminution of ‘hierarchies or status’ (Hirst and Humphreys, p.1506).

Elsewhere, the devastation has been unleashed. According to Dale and Burrell, seven miles of internal walls in the UK Treasury were removed, ‘literally dismantling the ‘corridors of power’’ (Dale and Burrell, 2010). To justify this destruction, those arguments of productivity and enhanced yield emerge from their 1950’s winding sheet. But here the grain and seed so eagerly sought are those of ‘interactive, complex, open-ended teamwork’ and the diminution of ‘hierarchies or status’ (Hirst and Humphreys, p.1506).

In Hirst and Humphrey’s study of ‘dehedging’ at a UK local authority’s new HQ, there are plaintive echoes of more literal counterparts. As part of the move, ‘de-cluttering’ was encouraged, with sanctions for those ‘who failed to leave their workspace entirely clear of all paperwork and personal items’ (Hirst and Humphreys, p.1516). You can almost hear the bushwhacker’s whine and roar. Yet, three years after this pruning and scraping, ‘many staff had ‘nested’’, their belongings defiantly on display. It is a suggestive metaphor – the domesticity of home and security once more restored to the open, wind-blasted ‘field’.

Elsewhere, the benefits of the prairie office plain are equally elusive. In a new study of food and eating in the workplace, Harriet Shortt observes how, in an open plan office ‘designed with collaboration, togetherness and teamwork in mind’ (Shortt, p.11), one interviewee talked of the loneliness and sense of exclusion such an environment engenders. It is the cake and pastries brought from home and shared ‘on desks and on locker tops’, that bring people back together and reconnect conversations – like birds noisily congregating around the hedgerow’s larder of haws, hips and sloes.

As we have seen, the hedgeless field offers exposure and threat: all who cross or linger are open to the gaze of others. In a recent paper, Hirst and Schwabenland reveal that in a newly configured office, visibility meant that ‘being observed was a constant possibility’ (Hirst and Schwabenland, p.170). For some women this visibility was ‘perceived as uncomfortable or oppressive’ with attendees for job interviews being ‘marked’ for their attractiveness by men in the team (Hirst and Schwabenland, p.170). Similarly, Kingma, in a study of the effects of ‘new ways of working’ in a Dutch insurance company, quoted employees who felt they were ‘constantly being watched’ (Kingma, p.16).

In an echo of this, Shortt notes how several women working flexible arrangements found the hot-desking arrangements exclusionary. They described themselves as ‘nomads’, ‘wandering around the office to find a desk’ – rootless travellers deprived of a home base or shelter from the workplace storm.

So maybe we should campaign for the return of our metaphoric organisational hedges. Allen identified ‘washrooms, copying machines, coffeepots, cafeterias’ as ‘interaction-promoting facilities’ that draw people to them increasing the occurrence of chance encounters and unintended communication (Allen, p.248). And these ‘hedgerow rendezvous’ have value: they are the ‘prime vehicle for transmitting ideas, concepts, and other information necessary for ensuring effective work performance’ (Allen, p.269).

So maybe we should campaign for the return of our metaphoric organisational hedges. Allen identified ‘washrooms, copying machines, coffeepots, cafeterias’ as ‘interaction-promoting facilities’ that draw people to them increasing the occurrence of chance encounters and unintended communication (Allen, p.248). And these ‘hedgerow rendezvous’ have value: they are the ‘prime vehicle for transmitting ideas, concepts, and other information necessary for ensuring effective work performance’ (Allen, p.269).

Hillier stresses the importance of the ‘weak ties’ generated by buildings. These connections to ‘people that one does not know one needs to talk to’ are more likely to break the boundaries of knowledge that solidify when projects, functions and departments are localised (Quoted in Kornberger and Clegg, p.1105). The ‘generative buildings’ that result evoke ‘chaotic, ambiguous, and incomplete space’. It is in these margins – where people who are ‘normally separated exchange ideas and concepts’ – that ‘creative organising and positive power happens’ (Kornberger and Clegg, p.1106). This is fluid, liquid, organic space or, if you prefer, the organisational hedgerows which shelter chance, promise and threat.

For, in these peculiarly liquid times of flux and change, it is important ‘to move quickly and easily across the team boundary’ (Dibble and Gibson, p.926). Contract workers, consultants, fledgling, entrepreneurial ventures all require borders that are permeable and porous. And, like the variety of flora and fauna engendered by the hedgerow, these organisational boundaries can be similarly diverse. Their form may be social, cultural, physical while the flow can involve people, information, resources and status (Dibble and Gibson, p.929).

So, if you hear the bushwhacker’s roar, remember the power of elder, dogwood, hazel and sweet briar. For it in these interlacing boundaries, fertile, pliable and everlastingly liminal, that the inventive and cunning will find the shaded gaps that lead to invention and, maybe, salvation.

Now the hedgerow is blanched for an hour with transitory blossom/Of Snow, a bloom more sudden/Than that of summer

Allen, Thomas J. (1977), Managing the flow of information. MIT Press.

Clifford, S. and King, A. (2006), England in particular: a celebration of the commonplace, the local, the vernacular and the distinctive. Hodder & Stoughton.

Dale, K. and Burrell, G. (2010) ‘All together, altogether better’: the ideal of ‘community’ in the spatial reorganization of the workplace’, in van Marrewijk, A. and Yanow, D. (eds.) Organizational spaces: dematerialising the workaday world. Edward Elgar.

Dibble, R. and Gibson, C. B. (2018) ‘Crossing team boundaries: a theoretical model of team boundary permeability and a discussion of why it matters’, Human Relations, 71(7), pp. 925–950.

Eliot, T.S. (1944) ‘Little Gidding’, in Four Quartets. Faber.

Hirst, A. and Humphreys, M. (2013) ‘Putting power in its place: the centrality of edgelands’, Organization Studies, 34(10), pp. 1505–1527.

Hirst, A. and Schwabenland, C. (2018) ‘Doing gender in the “new office”’, Gender, Work and Organization, 25(2), pp. 159–176.

Hurdley, R. (2010) ‘The power of corridors: connecting doors, mobilising materials, plotting openness’, The Sociological Review, 58(1), pp. 45–64.

Kaczmarczyk, K. and Salvoni, M. (2016) ‘Hedge mazes and landscape gardens as cultural boundary objects’, Sign Systems Studies, 44(12), pp. 53–68.

Kingma, S. (2018) ‘New ways of working (NWW): work space and cultural change in virtualizing organizations’, Culture and Organization, (Online), pp. 1-24.

Kornberger, M. and Clegg, S. R. (2004) ‘Bringing space back in: organizing the generative building’, Organization Studies, 25(7), pp. 1095–1114.

Macfarlane, R. (2015), Landmarks. Hamish Hamilton

Shortt, H. (2018) ‘Cake and the open plan office: a foodscape of work through a Lefebvrian lens’, in: Kingma, S., Dale, K. and Wasserman, V., eds. (2018) Organizational space and beyond: The significance of Henri Lefebvre for organizational studies. Routledge [In Press].

But then, this should not surprise us. For the crossroads is a place of contradictions. A liminal space caught between borders and possibilities. It is a ‘real place between imaginary places – points of departure and arrival’ (Komunyakaa, p.5). We stand poised between where we have been and where we might, in the future, find ourselves. This is the ‘intersection of the timeless moment’ (Eliot, p.42). Opportunity, danger, enchantment, despair, salvation and damnation insinuate themselves, like a twilight mist, around our lonely fingerpost.

But then, this should not surprise us. For the crossroads is a place of contradictions. A liminal space caught between borders and possibilities. It is a ‘real place between imaginary places – points of departure and arrival’ (Komunyakaa, p.5). We stand poised between where we have been and where we might, in the future, find ourselves. This is the ‘intersection of the timeless moment’ (Eliot, p.42). Opportunity, danger, enchantment, despair, salvation and damnation insinuate themselves, like a twilight mist, around our lonely fingerpost. The ambiguity of the crossroads is also seen in the tradition of burying of suicides. Halliday notes that although the law in England stipulated that a suicide should be buried in the King’s highway, the chosen site was often a crossroad by a parish boundary (Halliday, p.82). I frequently pass one such site. In 1785, Richard Knobbs, a brickmaker in the Norfolk village of Hempnall, was suspected of murdering his son and hanged himself from a tree. The junction where he is buried is still known as Nobb’s Corner. Halliday argues that such interment acted as a deterrent. Excluded from the community of a churchyard, burial in a ‘remote, anonymous grave without a funeral was a casting-out; the person no longer belonged to society’ (Halliday p.82). Yet, maybe, such a place provided comfort too: the topographical cross bestowing some remnant of sanctity on the lost and, in every way, marginalised.

The ambiguity of the crossroads is also seen in the tradition of burying of suicides. Halliday notes that although the law in England stipulated that a suicide should be buried in the King’s highway, the chosen site was often a crossroad by a parish boundary (Halliday, p.82). I frequently pass one such site. In 1785, Richard Knobbs, a brickmaker in the Norfolk village of Hempnall, was suspected of murdering his son and hanged himself from a tree. The junction where he is buried is still known as Nobb’s Corner. Halliday argues that such interment acted as a deterrent. Excluded from the community of a churchyard, burial in a ‘remote, anonymous grave without a funeral was a casting-out; the person no longer belonged to society’ (Halliday p.82). Yet, maybe, such a place provided comfort too: the topographical cross bestowing some remnant of sanctity on the lost and, in every way, marginalised. Stepping between floors, we are, spatially, betwixt and between: poised between one zone of experience and another. Or, as AA Milne (and, yes, the Muppets) phrased it: ‘It isn’t really anywhere! It’s somewhere else instead!’ In a recent Radio 4 Thought for the Day broadcast, Rabbi Dr Naftali Brawer describes the painting by the Baroque artist Jusepe de Ribera called Jacob’s Dream. The sleeping Jacob dreams of a ladder that climbs to heavens with angels ascending and descending. Brawer draws attention to how Ribera depicts Jacob’s face: it ‘exquisitely captures the betwixt and between of liminality, reflecting Jacob’s suspension between two realities; the terrestrial and the celestial.’

Stepping between floors, we are, spatially, betwixt and between: poised between one zone of experience and another. Or, as AA Milne (and, yes, the Muppets) phrased it: ‘It isn’t really anywhere! It’s somewhere else instead!’ In a recent Radio 4 Thought for the Day broadcast, Rabbi Dr Naftali Brawer describes the painting by the Baroque artist Jusepe de Ribera called Jacob’s Dream. The sleeping Jacob dreams of a ladder that climbs to heavens with angels ascending and descending. Brawer draws attention to how Ribera depicts Jacob’s face: it ‘exquisitely captures the betwixt and between of liminality, reflecting Jacob’s suspension between two realities; the terrestrial and the celestial.’ The staircase serves as a vertical

The staircase serves as a vertical  In a perceptive analysis of white spaces, Connelan notes the visceral reaction of one interviewee to the staircase in an art school: it ‘gives me the creeps, it reminds me of [the detention centre the person was incarcerated in] (Connelan, p.1543). There is a ‘brutality inscribed into the identity-less space’. The blank institutional whiteness of steps and stairs create a stark backdrop against which it is easy to be seen. You are isolated, silhouetted, the object of the carceral gaze. Here, white materialises power and exerts control. This creates not Foucault’s mobile panopticon but a ‘ubiquitous panopticon’ in which ‘watchfulness is everywhere and nowhere’ (Connelan, p.1545). The staircase encourages us both to linger and to escape.

In a perceptive analysis of white spaces, Connelan notes the visceral reaction of one interviewee to the staircase in an art school: it ‘gives me the creeps, it reminds me of [the detention centre the person was incarcerated in] (Connelan, p.1543). There is a ‘brutality inscribed into the identity-less space’. The blank institutional whiteness of steps and stairs create a stark backdrop against which it is easy to be seen. You are isolated, silhouetted, the object of the carceral gaze. Here, white materialises power and exerts control. This creates not Foucault’s mobile panopticon but a ‘ubiquitous panopticon’ in which ‘watchfulness is everywhere and nowhere’ (Connelan, p.1545). The staircase encourages us both to linger and to escape. We have seen how the corridor is a place that welcomes

We have seen how the corridor is a place that welcomes  Of course, we could read this artwork in another way. By encouraging us to navigate the corridor in a physically prescribed way, we are reminded how space acts as the ‘materialization of power relations’ (Taylor and Spicer, p.330). In Hurdley’s broadcast, the curator of Tyntesfield House describes how the corridor to the ‘virgins’ wing’ (where the female servants lived) was ‘protected’ by the Foucaldian panopticon of the cook’s bedroom: the senitel who detects and deters transgressive behaviour. In other grand houses, corridors are used to demonstrate monetary wealth and cultural learning. At Chatsworth, the Chapel Corridor evokes a grand collector’s gallery bringing together sumptious art works from the Devonshire Collection.

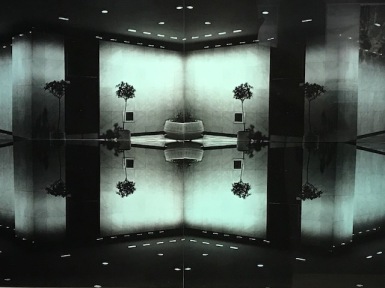

Of course, we could read this artwork in another way. By encouraging us to navigate the corridor in a physically prescribed way, we are reminded how space acts as the ‘materialization of power relations’ (Taylor and Spicer, p.330). In Hurdley’s broadcast, the curator of Tyntesfield House describes how the corridor to the ‘virgins’ wing’ (where the female servants lived) was ‘protected’ by the Foucaldian panopticon of the cook’s bedroom: the senitel who detects and deters transgressive behaviour. In other grand houses, corridors are used to demonstrate monetary wealth and cultural learning. At Chatsworth, the Chapel Corridor evokes a grand collector’s gallery bringing together sumptious art works from the Devonshire Collection. The scent of the uncanny also infuses our quotidian places of work. Should we ever visit after hours or at the week-end, they always invoke, I feel, a sense of the strange. And this is most apparent in the corridors: quiet, denuded, almost sentient in their calm. This effect heightens perception: sounds are subtly amplified; and the signage and art work somehow appear more prominent. We might attribute this to the failure of presence – ‘there is nothing present where there should be something’ (Fisher, p.61). This quality of the eerie is forensically explored by the artist Tim Head in a series of photographic collages showing de-humanised spaces: empty corporate receptions, hotel entrances, underground car parks. Enhanced by pale tinting, the collages portray the uncanny and alien while evoking the melancholy of lost and half-imagined futures.

The scent of the uncanny also infuses our quotidian places of work. Should we ever visit after hours or at the week-end, they always invoke, I feel, a sense of the strange. And this is most apparent in the corridors: quiet, denuded, almost sentient in their calm. This effect heightens perception: sounds are subtly amplified; and the signage and art work somehow appear more prominent. We might attribute this to the failure of presence – ‘there is nothing present where there should be something’ (Fisher, p.61). This quality of the eerie is forensically explored by the artist Tim Head in a series of photographic collages showing de-humanised spaces: empty corporate receptions, hotel entrances, underground car parks. Enhanced by pale tinting, the collages portray the uncanny and alien while evoking the melancholy of lost and half-imagined futures. But these suggestive, liminal ruins are betwixt and between in other ways. Their journey of transition is constant as agents such as wind, rain, lichen, moss, birds and insects recast their identities and ‘transform the qualities of matter’ (DeSilvey and Edensor, p.477). This is not necessarily a cruel or pitiless destruction. Looking into a marble fountain,there is ‘intimacy in the contact’ between stone and water that ‘here produces a gleaming surface veined with unsuspected colours, here magnifies fossil or granular structure’ (Stokes, p.26). Ruination can be gentle, caressive, revelatory.

But these suggestive, liminal ruins are betwixt and between in other ways. Their journey of transition is constant as agents such as wind, rain, lichen, moss, birds and insects recast their identities and ‘transform the qualities of matter’ (DeSilvey and Edensor, p.477). This is not necessarily a cruel or pitiless destruction. Looking into a marble fountain,there is ‘intimacy in the contact’ between stone and water that ‘here produces a gleaming surface veined with unsuspected colours, here magnifies fossil or granular structure’ (Stokes, p.26). Ruination can be gentle, caressive, revelatory. For this is a place where the visual is less privileged and where, unlike the usual tourist spaces, ‘the tactile, auditory and aromatic qualities of materiality’ are enhanced (Edensor, 2007, p.219). We are keen to the sound of the strimmer in the overgrown churchyard; the smell of the cut grass in the porch; the feel of the twig that bends underfoot as we navigate around fallen gravestones. This is Lefebvre’s perceived space – the ‘phenomenologically experienced spaces, that may be taken for granted through the habits of the body’ (Dale and Burrell, p.8). Note how we stoop past the shrub overhanging the south door – an automatic, reflex action.

For this is a place where the visual is less privileged and where, unlike the usual tourist spaces, ‘the tactile, auditory and aromatic qualities of materiality’ are enhanced (Edensor, 2007, p.219). We are keen to the sound of the strimmer in the overgrown churchyard; the smell of the cut grass in the porch; the feel of the twig that bends underfoot as we navigate around fallen gravestones. This is Lefebvre’s perceived space – the ‘phenomenologically experienced spaces, that may be taken for granted through the habits of the body’ (Dale and Burrell, p.8). Note how we stoop past the shrub overhanging the south door – an automatic, reflex action.