Marsh, mire, fen, bog, slough, morass and wetland. These are liminal landscapes. Places of making and unmaking where water cedes to land and land to water. The world here is never topographically still. Waterlands are ‘fungible’ and ‘highly motile spaces’ (Leyshon, pp.155-156). And this terrain is not to be trusted. It demands caution, respect and propitiation. Among the sedge, reed and rush, we hear the trickster’s laugh; for the ground underfoot is literally (and materially) ‘shifty’.

In the wetlands, nothing is what it seems. While investigating the Hound of the Baskervilles, Dr Watson comments that Dartmoor’s Grimpen Mire looks a rare place for a gallop. It takes the minatory Stapleton to caution that ‘a false step yonder means death to man or beast’ (Conan Doyle, p.82). For this is not a passive land. This bog is alive, infused with agency and vengeful will – it possesses a ‘tenacious grip’ wielded by a ‘malignant hand’ (p. 179). This potency is recognised by Daisy Johnson in the short story Starver where the eels caught on the draining of the fens refuse to eat: ‘it was a calling down of something upon the draining’ and some said they ‘heard words coming from the ground as the water was pumped away’ (Johnson, loc 39).

In the wetlands, nothing is what it seems. While investigating the Hound of the Baskervilles, Dr Watson comments that Dartmoor’s Grimpen Mire looks a rare place for a gallop. It takes the minatory Stapleton to caution that ‘a false step yonder means death to man or beast’ (Conan Doyle, p.82). For this is not a passive land. This bog is alive, infused with agency and vengeful will – it possesses a ‘tenacious grip’ wielded by a ‘malignant hand’ (p. 179). This potency is recognised by Daisy Johnson in the short story Starver where the eels caught on the draining of the fens refuse to eat: ‘it was a calling down of something upon the draining’ and some said they ‘heard words coming from the ground as the water was pumped away’ (Johnson, loc 39).

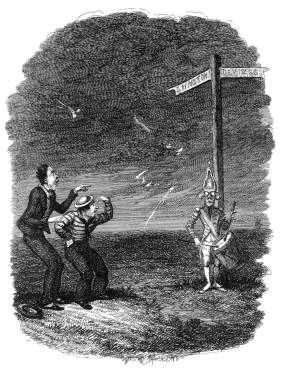

Folklore too recognises the spiteful malevolence of the wetlands. Those of the marsh tell stories of Will o’ the Wisp, Jack o’ Lantern, Spunkie, Pinket or Ignis Fatuus. This dangerous fairy takes delight in making unwary travellers lose their way – or their lives. Shifting its shape to promise beauty or riches, it tempts the foolish and gullible to flounder in the hungry, sucking bog.

Folklore too recognises the spiteful malevolence of the wetlands. Those of the marsh tell stories of Will o’ the Wisp, Jack o’ Lantern, Spunkie, Pinket or Ignis Fatuus. This dangerous fairy takes delight in making unwary travellers lose their way – or their lives. Shifting its shape to promise beauty or riches, it tempts the foolish and gullible to flounder in the hungry, sucking bog.

The marsh is a ‘thin place’ between the natural and the supernatural. Here votive offerings are made and chthonic gods placated. Shield, sword, helmet and torc are relinquished to water. These are the links that solder the living to the dead. And darker gifts are also tendered. In Denmark, more than 500 bog bodies have been found – sacrificial victims that are remarkably intact, preserved by the peat in which they were interred. In the liminal, ritual space of the wetlands, time too is not what it seems. These bodies slip their temporal constraints. Mummified flesh and bone make the Iron Age contemporary. Feature and expression vivid, startling – as if disturbed from yesterday’s sleep. And the past inhabits the present in other ways. In a series of poems inspired by the bog people, Seamus Heaney draws connections between ‘sacrifices to the Mother Goddess of Earth and the violent history of Northern Ireland’ (Morrison, p.47).

Out there in Jutland

In the old man killing parishes

I will feel lost,

Unhappy and at home

The Tollund Man

Fluxed between the material and immaterial, the past and the present, marsh, mire and estuary are border territories. And these ‘borders do not correspond to national boundaries, and papers and documents are unrequired at them’ (Macfarlane, p.78). Caught in this betwixt and between world, it is easy to lose your sense of what is and is not. The Broomway which, like Grimpen Mire, is only navigable by remembering ‘certain complex landmarks’, heads out to sea for three miles from the Essex coast before making landfall at Foulness Island. Swept ‘clean of the trace of passage twice daily’, this is a path that is no path (Macfarlane, p.61). In walking it, Robert Macfarlane experiences a ‘strange disorder of perception’: scale and distance twist and weld as ‘sand mimicked water, water mimicked sand, and the air duplicated the textures of both’ (Macfarlane, p.75).

In this ‘unbiddable and ‘unmappable’ physical terrain’ (Roberts, p.42), the expertise of one ‘whose knowledge is ambulatory’ (Andrews and Roberts, p.9) is required. Traversing the ambiguous and potentially dangerous Broomway, Macfarlane is aided by a guide; just as those crossing the ‘uncertain and treacherous topography of Morecombe Bay’ (Andrews and Roberts, p.7) seek the help of the Sand Pilot. Like initiates in a rite of passage, they ‘put their trust in an elder or master of ceremonies who ‘can ensure safe navigation and transit(ion)’ (p.8).

In this ‘unbiddable and ‘unmappable’ physical terrain’ (Roberts, p.42), the expertise of one ‘whose knowledge is ambulatory’ (Andrews and Roberts, p.9) is required. Traversing the ambiguous and potentially dangerous Broomway, Macfarlane is aided by a guide; just as those crossing the ‘uncertain and treacherous topography of Morecombe Bay’ (Andrews and Roberts, p.7) seek the help of the Sand Pilot. Like initiates in a rite of passage, they ‘put their trust in an elder or master of ceremonies who ‘can ensure safe navigation and transit(ion)’ (p.8).

And the consequences of unaided passage are severe. In 2004, twenty-three Chinese migrant workers were drowned while harvesting cockles on the sand and mud-flats of Morecombe Bay. This is the liminal compounded in on itself. For, as Roberts soberly observes, migrant workers are themselves liminal, occupying a ghostly ‘zone on the social and geographic margins of the nation; caught in the interstices of transnational space’ (Roberts, p.41).

The wetlands attract those, less innocent than the cockle pickers, but caught too in the shadows of the edgelands and margins. It is in the ‘dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates’ that Pip first encounters the escaped convict, Magwitch in Great Expectations (Dickens, p.35). Magwitch bears corporeal witness to the agency of this bleak marsh: he is ‘soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars’ (p.36). This is land that always exacts payment.

Magwitch’s crimes alert us that that this is also a place for transgression. Not far from where I write, you will find (although it may prove harder than you think) The Locks Inn in Geldeston. Marooned in the Waveney marshlands that separate Suffolk from Norfolk, this was (formerly) a site of cross-country smuggling and illegal prize-fighting.

The wetlands, like other liminal spaces, ‘fall outside of the geographic grid’ (Iedema et al). As Roberts note, the cultural and literary imaginaries of marsh, mire and estuary hold these as marginal and socially ‘empty’ spaces (Roberts, p.216). They feature the featureless which is why, in representations of the Norfolk Broads, the drainage mill and wherry have played such an important role ‘in the symbolic construction of place in a landscape otherwise characterised in terms of its flatness and lack of prominent (natural) topographic features’ (Roberts, p.217). These are the visual and cognitive equivalents of the firm sand, grass or moss that ensure confident navigation through quicksand and bog.

These spaces are also ‘empty’ in a utilitarian sense. They are ‘denuded of a rationalised function’ (Roberts, p.217). What are the wetlands for? And we see echoes of this in our own liminal, organisational spaces – the corporate shadows of marsh, mire and estuaries. In their study of how a bulge in a hospital corridor became a site of instruction and knowledge exchange, Iedema et al note that it ‘lacked functional definition’; it did not ‘embody strong indications to staff about what is to take place’ there (Iedema et al, p.53). Corridors, toilets, store-rooms, lifts, stairwells, kitchens, photocopier rooms – these are all spaces that do ‘not seem to serve a productive function’ from a rational, calculative perspective (Warnes, p.46). They embody, in a sense, ‘space out of space’ (Van Marrewijk and Yanow, p.10). Yet, like the wetlands they metaphorically reflect, these too are spaces of potency and energy – spaces for story, creativity, interaction, learning and transformation. Spaces too where we can lose ourselves but, unlike Grimpen Mire, always guarantee a safe return.

Andrews, H. and Robert, L. (2012) ‘Re-mapping liminality’, in Andrews, H. and Robert, L. (eds.) Liminal landscapes: travel, experiences and spaces in between. Routledge.

Conan Doyle, A. (1902), The hound of the Baskervilles. Pan.

Dickens, C. (1861), Great expectations. Penguin.

Heaney, S. (1980), ‘The Tollund Man’, in Selected poems: 1965-1975. Faber.

Iedema, R, Long, D and Carroll, K. (2010) ‘Corridor communication, spatial design and patient safety: enacting and managing complexities’, in van Marrewijk, A. and Yanow, D. (eds.) Organisational spaces: dematerialising the workaday world. Edward Elgar.

Leyshon, C. (2018), ‘Finding the coast: environmental governance and the characterisation of land and sea’, Area, 50(2), pp. 150-158.

Macfarlane, R. (2012), The old ways: a journey on foot. Hamish Hamilton.

Morrison, B. (1982), Seamus Heaney. Metheun.

Roberts, L. (2018), Spatial anthropology: excursions in liminal space. Rowman & Littlefield.

Van Marrewijk, A. and Yanow, D. (2010) ‘Introduction: the spatial turn in organizational studies’, in van Marrewijk, A. and Yanow, D. (eds.) Organizational spaces; rematerializing the workaday world. Edward Elgar.

Warnes, S. (2015) Exploring the lived dimension of organizational space: an ethonographic study of an English Cathedral. PhD thesis, University of Essex, UK.

And, like all liminal spaces, the beach offers promises of transformation. In Rob Shields’ fascinating analysis of Brighton’s cultural positioning, he argues how the Prince Regent, later George IV, popularised the ‘reputedly restorative powers of sea-bathing’ (Shield, p.75). For the sick and valetudinarian, this was a pilgrimage covenanting physical renewal. And the reward for the devoted traveller was the ‘Cure’: a programme of prescribed sea-dippings (the rites of the liminal phase) officiated by ‘Dippers’. These ‘priests’ carefully (or forcefully) assisted their charges from the bathing machines: ‘mediaries between two worlds, civilised land and the undisciplined waves’ (Shields, p.84).

And, like all liminal spaces, the beach offers promises of transformation. In Rob Shields’ fascinating analysis of Brighton’s cultural positioning, he argues how the Prince Regent, later George IV, popularised the ‘reputedly restorative powers of sea-bathing’ (Shield, p.75). For the sick and valetudinarian, this was a pilgrimage covenanting physical renewal. And the reward for the devoted traveller was the ‘Cure’: a programme of prescribed sea-dippings (the rites of the liminal phase) officiated by ‘Dippers’. These ‘priests’ carefully (or forcefully) assisted their charges from the bathing machines: ‘mediaries between two worlds, civilised land and the undisciplined waves’ (Shields, p.84). Remember though – the beach of summer becomes the beach of winter. And this brings more caliginous meanings. The borderlands and margins are ‘also places of anxiety replete with darker images of threat and danger.’ (Preston-Whyte, p.350). These ‘placeless places’ of No Man’s Land and crossroads – where the gibbet stands and the graves of suicides and witches lie – invite the liminal’s shadow (see Trubshaw, 1996). In M.R. James’ A Warning to the Curious and Oh, Whistle, and I’ll come to you, My Lad, the landscape of the beach reflects a ‘temporal instability’ where an artefact from the past has the power to exact a dreadful vengeance in the present.

Remember though – the beach of summer becomes the beach of winter. And this brings more caliginous meanings. The borderlands and margins are ‘also places of anxiety replete with darker images of threat and danger.’ (Preston-Whyte, p.350). These ‘placeless places’ of No Man’s Land and crossroads – where the gibbet stands and the graves of suicides and witches lie – invite the liminal’s shadow (see Trubshaw, 1996). In M.R. James’ A Warning to the Curious and Oh, Whistle, and I’ll come to you, My Lad, the landscape of the beach reflects a ‘temporal instability’ where an artefact from the past has the power to exact a dreadful vengeance in the present. The Barbican in London is a source of solace. Walking the grey, water-stained ramparts, I feel protected by its coarse solidity. The hard, excoriating drag of bush-hammered aggregate reassures rather than pains. This is a place – fittingly given its name – of defence, retreat and enclosure. In my more oneiric moments, I imagine a dystopian city of hand to hand fighting – a Stalingrad for a future age – with the Barbican providing the last refuge for defiance and resistance. With a morbid eye, I see the walkways and towers pitted by shellfire revealing the twisted steel rods within.

The Barbican in London is a source of solace. Walking the grey, water-stained ramparts, I feel protected by its coarse solidity. The hard, excoriating drag of bush-hammered aggregate reassures rather than pains. This is a place – fittingly given its name – of defence, retreat and enclosure. In my more oneiric moments, I imagine a dystopian city of hand to hand fighting – a Stalingrad for a future age – with the Barbican providing the last refuge for defiance and resistance. With a morbid eye, I see the walkways and towers pitted by shellfire revealing the twisted steel rods within. Several of these

Several of these  And, as we have intimated

And, as we have intimated  Such ghosts possess other objects too. A long time ago, I asked a colleague to identify an artefact that encapsulated our then organisation. After a pause, he spoke fondly of the chair that his former boss had left behind on retirement. Each time he saw it, he took strength from the memory of his mentor, guide and protector. It had what Weber called the ‘charisma’ of the object’ and Walter Benjamin, ‘the aura of the original’ (Bell, p.817). That chair was not just any chair; it contained a ‘kind of life’.

Such ghosts possess other objects too. A long time ago, I asked a colleague to identify an artefact that encapsulated our then organisation. After a pause, he spoke fondly of the chair that his former boss had left behind on retirement. Each time he saw it, he took strength from the memory of his mentor, guide and protector. It had what Weber called the ‘charisma’ of the object’ and Walter Benjamin, ‘the aura of the original’ (Bell, p.817). That chair was not just any chair; it contained a ‘kind of life’.