A Christmas Carol is a story spiced with the liminal. Scrooge, the not so eager and compliant liminar, is spatially and temporally removed from his everyday surroundings, counselled by wise and patient mentors, and emerges so transformed that a bewildered Bob Cratchit considers knocking him down with a ruler and ‘calling the people in the court for help and a strait-waistcoat’. And just as initiates in a rite of passage are structurally indiscernible (van Gennep, 1960 [1909]) (Turner, 1967), so Scrooge is literally invisible: as the Ghost of Christmas Past cautions him, the figures they encounter ‘have no consciousness of us’.

The liminal theme is introduced in the first sentence: ‘Marley was dead: to begin with’. But this point, like the coffin-nails to which the narrator refers, is repeatedly hammered home over the subsequent four paragraphs. The consequent doubt that arises through such over emphasis, rather than confirming the distinctions of life and death, intimates that such categories are not as fixed and immutable as we might optimistically imagine. And this classificatory uncertainty resonates through the whole novella as a tonal accompaniment to the state of anti-structure into which Scrooge progressively succumbs.

Indeed, even the weather confirms this sense of ambiguity. The fog — that ‘came pouring in at every chink and keyhole’ of Scrooge’s counting house — conceals and confuses. Even though ‘the court was of the narrowest’, the houses opposite are transmuted into ‘mere phantoms’ with the material and substantial rendered immaterial and insubstantial

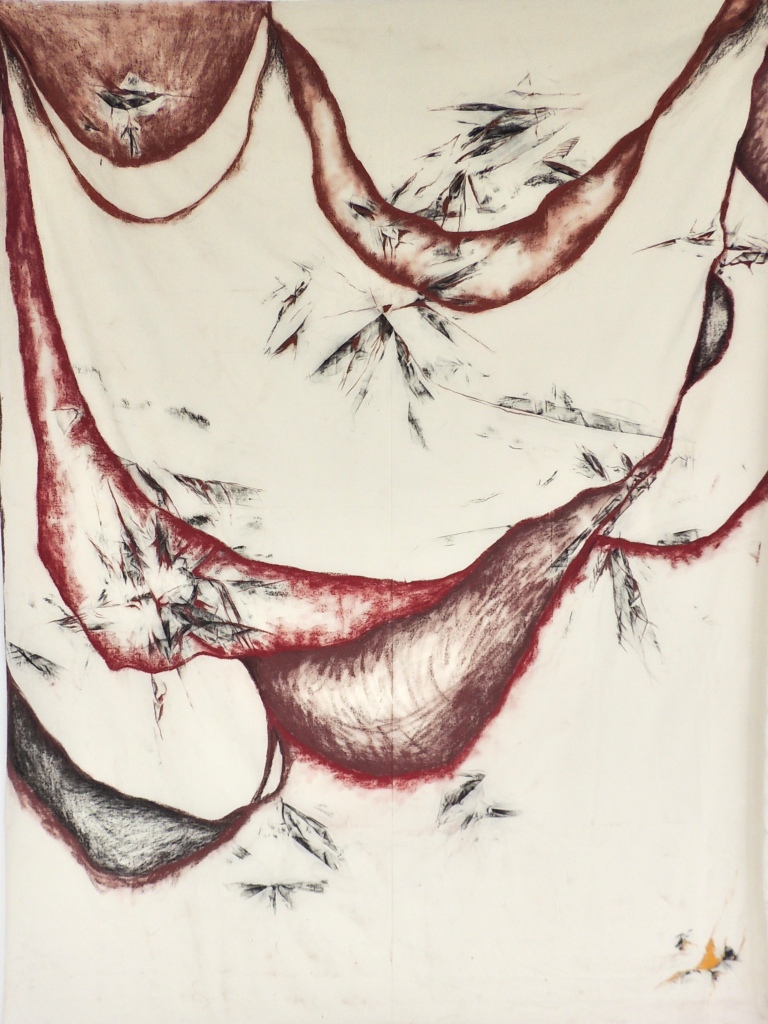

And, of course, ‘phantoms’ are at the heart of A Christmas Carol. But not just one but three — and, ghosts, as we have seen, are spectres of the liminal. As the ‘non-object, this non-present present, this being-there of an absent or departed one’ (Derrida, quoted in Orr, 2014, p. 1055), they ‘elide the distance between the actual and the imagined’ so that ‘frail and cherished distinctions collapse’ (Beer, quoted in Jackson, 1981, p. 69). And this particular ghostly trio of ghosts intensifies such ambiguity as the present is haunted, not just by the past but the future, and in a further dissolution of expected categories, by its own doppelganger: the Ghost of Christmas Present.

And let us consider too where we encounter the first spectre in the story. As Scrooge stands in the ‘fog and frost’ by the ‘black old gateway’ to his ‘gloomy suite of rooms’, the door knocker transforms into the face of Marley. The threshold, with its implication of a margin or edge between two states or spaces and the possibility of transition between the two, is the archetypal liminal space — Scrooge’s former business partner could hardly have selected a more symbolically resonant location in which to (de)materialise. And this ghostly preference for spaces betwixt and between the interior and exterior is confirmed by Marley’s phantasmal companions who appear at Scrooge’s window ‘wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went’.

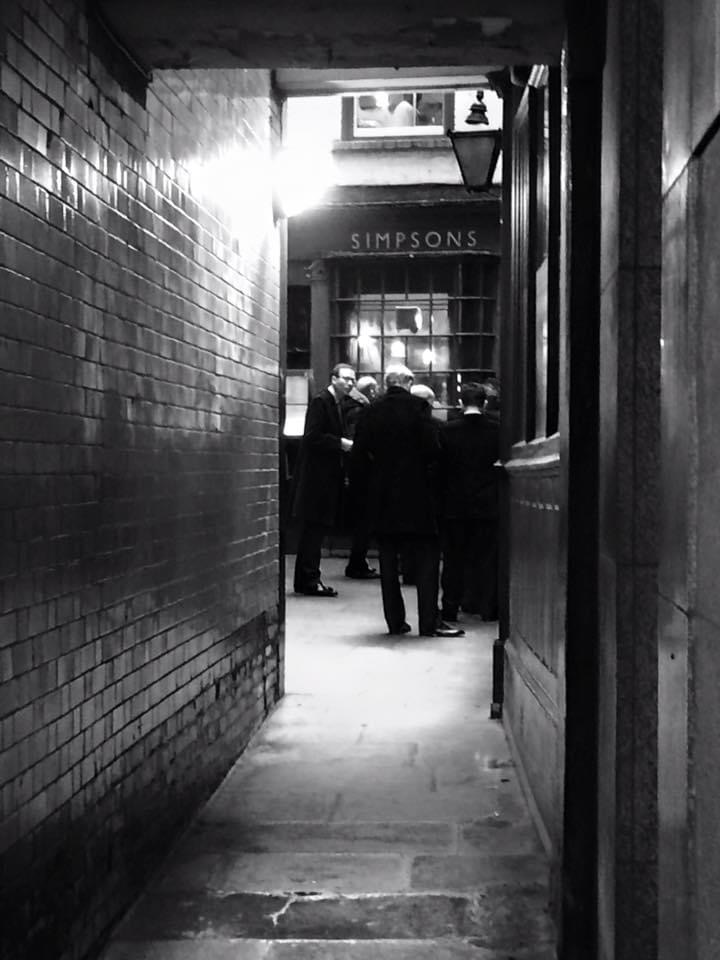

But A Christmas Carol is also, in many ways, a story of organisational practices. After all it starts and ends in Scooge’s counting house and offers a case study of both organisational and leadership change — even if the methodology deployed is unlikely to feature in any management textbook. And within this we can identify two intriguing examples of how organisational space is enacted as liminal. The first is glimpsed only briefly. After an invigorating Christmas Eve berating his nephew, two gentlemen calling for charitable donations and his brow-beaten clerk, Scrooge retires to a ‘melancholy tavern’ to take a ‘melancholy dinner’ and then ‘beguiled the rest of the evening with his banker’s book’. Perhaps this is an early example of ‘fluid and fissiparous’ organisational boundaries as work strays outside the counting house to colonise a space of social interaction: the ‘inside’ goes ‘outside’ (Fleming and Spicer, 2004, p. 79). Instead of a ‘squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner’, perhaps we should re-imagine Scrooge as an early adopter of mobile working. Replace the ‘melancholy tavern’ with a bright and festive Starbucks and his ‘banker’s book’ with a laptop (though I doubt it would be the latest model) and he is recast as one of Costas’ ‘kinetic elites’, adroitly navigating the porosity of work and non-work boundaries (Costas, 2013).

But if that is too much of an imaginative leap, let us explore the ‘office Christmas party’ hosted by Fezziwig, Scrooge’s beloved first employer. Such parties comprise both work and not work: a ‘relatively free space in which people can and do play, but it is also a space in which ‘fun’ has been institutionalized’ (Rosen, p. 468). Such a space can sanction the suspension or inversion of organisational hierarchies and the promise of transgressive activities such as dance, music, food and performance (although, as Hancock (2023) notes, such parties in the contemporary workplace are proving increasingly problematic). The confusion of work and non-work distinctions is pre-figured by the material transformation of the workplace as ‘every moveable was packed off…the floor was swept and watered, the lamps were trimmed, fuel was heaped upon the fire; and the warehouse was as snug, and warm, and dry, and bright as a ball-room’. Like Rothenburg’s Polish bar that shapeshifts from cafe to restaurant to nightclub during the course of the day (2000), so the identity of Scrooge’s place of work is rendered equally problematic: simultaneously both warehouse and ball-room. But the blurring of categories is short-lived. Following the forfeits, the porter, the Cold Roast and Cold Boiled, the dancing and the fiddling, as the clock strikes eleven, this ‘domestic ball broke up’ and, as the guests depart and the ‘cheerful voices died away’, Scrooge and his fellow apprentice, Dick ‘were left to their beds; which were under a counter in the back-shop’. After the liminal inversion of organisational norms, order and customary practice is restored — for, as Turner observes, liminal phases ‘invert but do not usually subvert the status quo’ (Turner, 1982, p. 42). Once the carnival is over, ‘normal order is quickly and completely restored’ (Rippin, quoting Bakhtin, p. 824).

And this brings us to the close of the novella as we return to Scrooge’s counting house. And here, the boundaries between work and social activities are once more subverted. But if earlier the workplace strayed outside to the tavern, the home has now strayed inside the office (see Attlee, 2022). The transformation of Scrooge’s leadership style (from directive and pace-setting to affiliative perhaps) is mirrored by the replacement of typical organisational activities — copying, accounting, drafting — with the more social, domestic behaviours of drinking a ‘bowl of smoking bishop’ by a roaring fire. Yet, if we view the unfolding of the story as a carnivalesque, liminal experience, normal service is all too quickly resumed. For despite Scrooge’s feelgood rite of passage, as Hancock intimates, the status quo of commerce, consumption and market economics emerge unscathed, if not reinforced (2023). Fittingly, for a tale where certainties dissolve and elide, it is a tale where both everything — and perhaps nothing — changes.

Attlee, E. (2022) Strayed homes: cultural histories of the domestic in public. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

Costas, J. (2013) ‘Problematizing mobility: a metaphor of stickiness, non-places and the kinetic elite’, Organization Studies, 34(10), pp. 1467–1485.

Dickens, C. (1971) The Christmas books: volume one. London: Penguin.

Fleming, P. and Spicer, A. (2004) ”You can checkout anytime, but you can never leave’: spatial boundaries in a high commitment organization’, Human Relations, 57(1), pp. 75–94.

Hancock, P. (2023) Organizing Christmas. New York: Routledge.

Jackson, J. (1981) Fantasy: the literature of subversion. London: Methuen.

Orr, K. (2014) ‘Local Government Chief Executives ’, Everyday hauntings : towards a theory of organizational ghosts’, Organization Studies, 35(7), pp. 1041–1061.

Rippin, A. (2011) ‘Ritualized Christmas headgear or “Pass me the tinsel, mother: it’s the office party tonight’, Organization, 18(6), pp. 823–832.

Rosen, M. (1988) ‘You asked for it: Christmas at the bosses’ expense’, Journal of Management Studies, 25(5), pp. 463–480.

Rottenburg, R. (2000) ‘Sitting in a bar’, Studies in Cultures, Organizations and Societies, 6(1), pp. 87–100.

Turner, V. (1967) The forest of symbols: aspects of Ndembu ritual. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Turner, V. (1982) From ritual to theatre: the human seriousness of play. New York: PAJ Publications.

Van Gennep, A. (1960[1909]) The rites of passage. Translated by M.K. Vizedom and G.L. Caffee. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.